Thank you to History major Sara Winik for being the first University of Michigan, Ann Arbor student to offer her contribution to our ongoing discourse on the Niger Delta.

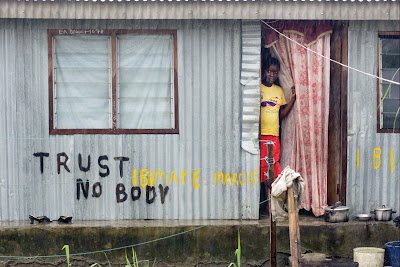

Sara: "From behind the curtain door is a young girl, curious but also reserved, peering at the photographer through the rain. This photograph is symbolic of many attitudes in the Niger Delta. The people of the region are the ones who suffer at the hands of all other groups; big oil companies, government, and militant groups. The people have no reason to trust any higher body in power because everyone else involved in the Niger Delta cycle are benefiting at the locals’ expense."

Sara: "The combination of these two scenes demonstrates the disparity between the wealthy in power and the poor Nigerians. The mother has no one to look to for help. The King, nevertheless, sits peaceful in the reception room of his palace while the people he is supposed to lead, suffer."

Sara: "The combination of these two scenes demonstrates the disparity between the wealthy in power and the poor Nigerians. The mother has no one to look to for help. The King, nevertheless, sits peaceful in the reception room of his palace while the people he is supposed to lead, suffer."

Sara: "Lastly, the photograph of MEND and another armed militant group depicts how even the people standing up to the oil companies and the government cannot be trusted. Although they appear similar, the two different militant groups can be distinguished from how they are holding their guns. The group on the left is pointing their guns down toward the other group whereas the militants in the boat on the right are pointing their guns to the sky. This photograph shows the internal differences amongst militant groups. The Nigerians are not organizing uprisings together. Instead, separate factions form that work together at times but mostly for profit not for the greater good of the region."

Thank you, Sara for your insights!

To read Sara's essay in its entirety, click below.

Sara Winik

History 247

3/29/09

Black Gold Paper

The Cycle of Trusting ‘No Body’ in the Niger Delta: Curse of the Black Gold

Ed Kashi’s pictures coupled with Michael Watt’s writings can be used together to see the cycle of mistrust in the Niger Delta that leads to suffering, injustice, and poverty. The people of the Niger Delta do not have anyone to represent them or represent their issues. The oil companies exploit the Nigerian environment, natural resources, and labor. The government benefits from big oil companies paying them off. Additionally, many militant youth groups who claim to be fighting for equality in the Niger Delta are actually benefiting from government and big oil companies’ bribes. The pictures and texts together portray this cycle.

One of the earliest pictures in The Curse of the Black Gold, is a picture on page 12-13 which depicts a metal house with bold black graffiti on the wall reading “Trust No Body.” From behind the curtain door is a young girl, curious but also reserved, peering at the photographer through the rain. This photograph is symbolic of many attitudes in the Niger Delta. The people of the region are the ones who suffer at the hands of all other groups; big oil companies, government, and militant groups. The people have no reason to trust any higher body in power because everyone else involved in the Niger Delta cycle are benefiting at the locals’ expense. Even Kashi, a photojournalist who is attempting to open the eyes of the world to the mistreatment of the Niger Delta, appears threatening to this little girl.

The history of the Niger Delta’s extractive economy as told in Ukoha Ukiwo’s “Empire of Commodities” further shows how the people have little to trust as seen in the above photograph. Ukiwo explains how at first the Portuguese entered the region to extract its spices and ivory. Then, by the 1700s, the population was used as slaves, following a transition into legitimate commerce in palm oil. Eventually, the European and Americans extracted oil starting in 1956. Ukiwo states that “the Niger Delta stands today-as it has for five centuries and more-at the epicenter of a violent economy of extraction,” (70). This article shows how historically, the people of the Niger Delta have been exploited. Therefore, the graffiti from the picture saying “trust No Body” reigns true in the fifteenth century as well as today.

Moreover, the juxtaposition of a picture of a King to a picture of an eighteen-year-old mother further shows how the people of the Niger Delta have no one to trust. King Egi of Ogabaland is shown sitting on a leather couch wearing a lavish red and gold shirt with a golden crown and leather shoes. Next to him is a toddler boy in pants and a white polo shirt playing on the couch (106-107). However, on the next spread is a young mom staring up at the camera in desperation. To her left is her two-year-old son barley clothed, sleeping on the floor (108-109). The combination of these two scenes demonstrates the disparity between the wealthy in power and the poor Nigerians. The mother has no one to look to for help. The King, nevertheless, sits peaceful in the reception room of his palace while the people he is supposed to lead, suffer.

The idea of the government benefiting at the expense of the civilians is seen in a quote by Alhaji Nuhu Ribadu, the Chairman of the Nigerian Economic And Financial Crimes Commission. This text supports the disparity of wealth and resources as represented in the photographs. In 2007 Ribadu stated, “the Nigerian state is not even corruption. It is organized crime,” (203). This quote describes how the corrupted state does not look out for the wellbeing of the population. Instead, like the picture of the well-dressed King, the government profits to the detriment of others. This connects back to the first photograph of the graffiti, as well. It shows how there is no one for the average young mother to look to for help. This type of exploitation in the Niger Delta has occurred continuously for decades.

Lastly, the photograph of MEND and another armed militant group depicts how even the people standing up to the oil companies and the government cannot be trusted. Both militant groups are photographed in motorboats with black masks and machine guns (214-215). Although they appear similar, the two different militant groups can be distinguished from how they are holding their guns. The group on the left is pointing their guns down toward the other group whereas the militants in the boat on the right are pointing their guns to the sky. This photograph shows the internal differences amongst militant groups. The Nigerians are not organizing uprisings together. Instead, separate factions form that work together at times but mostly for profit not for the greater good of the region.

Falix Tuodolo’s article, “Generation,” describes the dynamics of the youth groups in Nigeria as well. He explains how the past few decades have transferred a large amount of power from the chiefs to the youth. The youth “have inserted themselves between local communities and big business and between local communities and government,” (114). However, Tuodolo also states that the youth groups compete with one another for “power and supremacy,” (115). This proves, as seen in the picture of the two militant groups working together but still weary of one another, that the groups alleged goals of providing equality to the people never actually reach the people. Instead, the militant groups take power for themselves and are another sphere of influence that the Nigerian people cannot trust.

The pictures combined with the texts in the Curse of the Black Gold work in tangent to depict the Nigerian peoples’ inability to trust any higher power in the region. The oil companies exploit the land and people, the government profits off of the oil companies, and the militant groups take advantage of the oil companies. In the end, it is the Nigerian people who live in poverty and face unequal conditions. As seen in the saying on the metal house the Nigerian people “Trust No Body,” because all the groups are fighting for power and profits not the Nigerian population’s interests.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Sara - The First Student Voice!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Dear Sara, thanks for being the brave one and hope you're not alone in posting the essays. I just have to correct one point you made about the last image of the militants. In fact, all the armed men in that photo are with MEND and are not part of competing groups. Your reading of that image in that way, in and of itself, is interesting to me. It shows the way images can be interpreted differently by different eyes. Also, it supports the process I want to take advantage of here, which is to allow others to review our work and either correct or confirm or just add insights and facts. thanks! ed

Post a Comment